The brain does not age linearly – and that is precisely its strength

Why does learning new languages often feel effortless at a young age, while later in life it requires significantly more effort? And why do some people remain mentally sharp well into old age, while others experience cognitive limitations much earlier?

Current neuroscientific research provides a surprising answer: the human brain does not age evenly. Instead, it develops through clearly distinguishable phases marked by critical turning points.

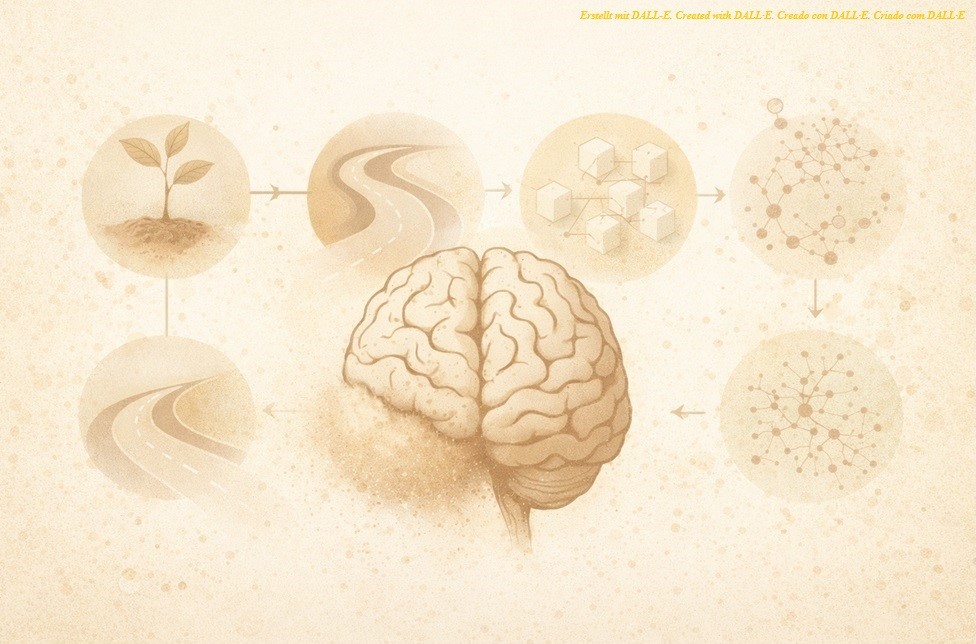

A study published in Nature Communications in December 2024 by the University of Cambridge shows that the brain undergoes five characteristic developmental phases over the course of life, separated by four major transitions occurring at approximately 9, 32, 66 and 83 years of age.

This article places the scientific findings in context and explains why they are relevant for long-term brain health.

The research: how five brain phases were identified

For the study, researchers analysed brain scans from nearly 4,000 individuals ranging from birth to around 90 years of age. The analysis focused on two key neurobiological parameters:

-

Myelin: a fatty insulating layer surrounding nerve fibres that determines the speed of neural signals

-

Water movement along nerve fibres: an indicator of how efficiently different brain regions communicate

By evaluating these data across several decades of life, researchers were able to precisely map changes in brain structure and connectivity.

“At different points in life, the brain is expected to perform different tasks,” explains Alexa Mousley, lead author of the study at the University of Cambridge.

The five phases of the brain and their turning points

Phase 1: Birth to around 9 years – reorganisation and selection

During early childhood, the brain undergoes intense structural reorganisation. The number of synapses decreases significantly, while connections that are frequently used are selectively strengthened. This process is known as synaptic pruning.

Figuratively speaking, it resembles a gardener tending an overgrown garden: unnecessary branches are removed so that the most important plants receive more light, space and nutrients. This results in stable and efficient neural networks.

This remodelling process has been associated in research with neurodevelopmental disorders, although causal relationships have not yet been conclusively established.

Turning point 1: around 9 years

The transition from fundamental restructuring to efficient organisation.

Phase 2: Adolescence to around 32 years – peak efficiency

Contrary to common assumptions, neurological adolescence does not end in the teenage years, but extends into early adulthood.

During this phase, the brain reaches its highest level of efficiency. Neural connections increasingly follow the shortest and most effective communication pathways.

This phase can be compared to a perfectly planned road network: direct routes, minimal detours and smooth information flow between all major hubs. White matter continues to develop, allowing information processing to be particularly fast and precise.

“Later phases are not worse – they simply serve different functions,” Mousley emphasises.

The unusually long adolescent phase in humans, compared to other mammals, is considered a key foundation for complex thinking, creativity and adaptability.

Turning point 2: around 32 years

The end of peak efficiency and the beginning of a stable phase.

Phase 3: Adulthood from around 32 to 66 years – stability and consistency

This life phase is characterised by remarkable structural stability. Major remodelling processes are largely absent, and neural networks function consistently.

Personality traits and cognitive abilities also show relatively little change during this period. From a preventive health perspective, this phase is particularly relevant, as long-term lifestyle factors can have lasting effects.

Turning point 3: around 66 years

The beginning of new structural adaptations.

Phase 4: Early ageing from around 66 to 83 years – reorganisation of connectivity

From the late sixties onward, changes in white matter structure become more pronounced. Neural connectivity is partially reorganised and increasingly clustered into smaller functional units. Communication shifts toward smaller, more tightly connected subnetworks.

“The division into smaller, locally well-connected groups increases,” Mousley explains.

These changes are associated with age-related conditions such as hypertension and neurodegenerative processes.

Turning point 4: around 83 years

Increasing fragmentation of neural communication.

Phase 5: Late ageing from around 83 years – adaptation to limited resources

In the final phase, global connectivity continues to decline. Certain key regions assume a central role in information processing.

Mousley compares this state to a public transport system in which some direct bus routes are discontinued, requiring multiple transfers for journeys that were once direct.

Cognitive processes such as memory retrieval and reaction speed may slow, although individual differences remain substantial.

What the turning points mean for brain health

No rigid age boundaries

The ages mentioned are based on statistical averages. Individual factors such as genetics, education, nutrition, physical activity and social engagement significantly influence actual trajectories.

“In medicine, the average is rarely the right benchmark for individuals,” explains neuroscientist Richard Betzel from the University of Minnesota.

Prevention across the entire lifespan

The identified phases highlight that there are meaningful opportunities to support brain health at every stage of life – from early stimulation and lifelong learning to physical activity and social interaction in later years.

Nutrition as a supportive factor

Although the study itself does not provide dietary recommendations, numerous other research findings indicate that a balanced diet with adequate protein intake, dietary fibre, healthy fats and antioxidant-rich plant compounds can contribute meaningfully to brain health.

This scientific perspective aligns with the philosophy of UNE Foods, which approaches functional nutrition holistically – as support for metabolism, the gut–brain axis and long-term vitality.

Conclusion: a dynamic organ throughout life

Dividing the brain into five phases with four turning points highlights that neural development and adaptation are lifelong processes.

Each phase brings its own strengths and challenges. Understanding these changes can help establish realistic expectations and place preventive measures in the appropriate context.

The brain remains adaptable – not indefinitely, but far longer than previously assumed.

Regardless of the phase one is in, it is never too early and never too late to care for brain health.

Sources:

Mousley A et al. Lifespan trajectories of the human connectome. Nature Communications 2024.

University of Cambridge. Press release, December 2024.

Legal notice: This article is intended for general informational purposes only and does not replace medical or therapeutic advice. For health-related questions, qualified professionals should be consulted.

Das könnte dich auch interessieren

18. May 2025

What are Sweeteners & Sugar Alcohols?

What are Sweeteners and Sugar Alcohols? Sweeteners and sugar alcohols are often seen as…

12. May 2025

5 a Day: What’s Behind the Fruit & Vegetable Recommendation?

The “5 a day” recommendation is familiar to many, but only few know where it comes from,…

7. April 2025

Wheat and Wheat Protein: Facts, Misconceptions and Real Insights

Wheat – An Ancient Grain with History Wheat protein is more than just gluten – it’s a…